You are here

Thinking Spaces: Exhibiting as the Last Discipline in Co-Design

Museums are often perceived as rather antiquated yet the statistics don’t confirm this stereotype since visiting museums is currently the most popular cultural activity in Switzerland. What responsibilities do museums have and in what way do they already fulfil them? In addition to the classical tasks of collecting and imparting knowledge, museums today have other more complex social tasks to fulfil.

The museum as social container

In order to reach as many people as possible, a museum today has to step out of its "comfort zone", dismantle social barriers and obstacles and open itself up to a heterogeneous, multicultural audience. As exhibition makers we have to ask ourselves repeatedly how we can break down boundaries and make exhibitions as accessible to the public as possible. Every visitor should feel welcome. It is not just the experienced gaze that is to be catered to; all visitors, regardless of their individual backgrounds and prior knowledge should be able to gain an understanding of the space, the works and their narratives.

The museum of today is a platform serving the exchange of knowledge in several different ways. Our understanding of a museum is therefore profoundly anti-hierarchical: we seek a dialogue with the audience. The concept of co-space is more appropriate to the institution of the museum than to some other establishments; the museum as a living, emotional, collaborative and constantly changing place is a place of multi-functionality, multiculturalism and togetherness.

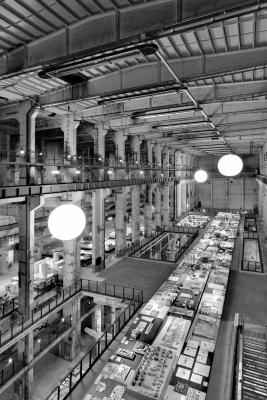

For the Realstadt exhibition that explored the topic of urban utopias we looked for — and found — a venue that wasn’t a museum but rather a former power station in Berlin Mitte. This authentic building became in itself a hugely impressive exhibit and an atmospheric setting for an incredible variety of architectural utopias. The visitors immersed themselves in its industrial ruins, mingled with the models and objects, filled the spaces and became part of the show’s unusual presentation.

The narrative co-space

We are living at the beginning of the digital age. The perceptual habits and capabilities of today’s public differ significantly from that of 10 or 20 years ago. We are now accustomed to receive on several different channels at the same time. With digitization the overlap of physical and digital space has become the norm. Moreover what is technically feasible and possible has been expanded and simplified. New media allow for diverse and individual mediation strategies. Visitors choose what aspect of a particular theme they are interested in and narrative forms come from a multitude of perspectives; nevertheless, the original object in its spatial setting remains the starting point for every visitor experience. Since museums can only show historical objects outside of their original context, augmented reality can fill a gap that must otherwise be left to the visitors’ imagination. The superimposition of the real object and the virtual contextual level contributes to the illustration of the narrative. Knowledge can in this way be communicated and perceived in multi-faceted or even partially customised ways.

The display of archaeological artefacts requires extensive explanations. Shards, bones or pieces of wood reveal little about themselves and the former times from which they originate. In the two visitor centres we designed — Nebra Ark and Paläon Research and Experience Center Schöningen Spears — narrative is at the forefront. Through the superimposition of real archaeological findings with illustrated narratives (models, animations or illustrations), the visitors’ imagination is triggered and history becomes something that can be experienced.

Collective Intelligence

Exhibition designers are always in essence laypersons when it comes to theme of each exhibition. Working together with people from a wide range of disciplines presents them with new challenges. The way these multiple perspectives and interests connect around a central motif makes the process of designing an exhibition unique: scientific, historical, architectural, curatorial or conservational aspects (to name but a few) influence the design, to some extent significantly. Exhibition design therefore doesn’t only mean room and display case design but it includes a lot more; from content concept, through selection of objects, to the definition of mediation strategies. The most successful exhibitions always come about as a result of the greatest possible collective intelligence.

The new design of the permanent exhibition at the Buchenwald Memorial clearly shows the complexity of this line of work. Several levels of design and mediation come together here. The exhibition is about remembrance but also about informing. It demonstrates, creates places of contemplation to commemorate the victims, creates disruptions and spaces for thinking — the emptiness left behind by this dark chapter in history becomes tangible.

Elements of an exhibition

The space is the starting point for every exhibition design. How architecture is used to circulate in the space is always of great symbolic significance. Will the architecture showcase itself or will it be overlaid with a new spatial intervention? What unites our exhibition spaces is the idea that in some ways they are like installations. We often find our inspiration in art. Artistic interventions move, disturb and engage the audience. When designing exhibitions the placement of objects in the room and the atmosphere generated always come first. Exhibitions are never "forever". The topicality of the themes explored and their narrative form change over time. Objects and things travel around the world and are presented in very varied places.

The exhibition REN. Good Guys — Good Design played with the aesthetics of objects. Contemporary design objects from China and the western world met and "communicated" with one another in a "cloud". New objects, designs and unique pieces were especially developed for this exhibition, for example a large-format wallpaper of reinterpreted Asian motifs and colours blended with Western textile art that provided an atmospheric and aesthetic way to kick off the exhibition.

The triad of object, presentation and space defines the overall impression of an exhibition, generates the first impression and determines the narrative. The mediation of content only ever comes second. We believe in the aesthetic power of an exhibition. We want to create spaces that have a high aesthetic value and whose function is to create an atmosphere. Our aspiration is to make a statement and take a stance that goes beyond mere explanation or scientific mediation. We don’t want to produce generic solutions but rather provide "tailor-made" answers that do justice to the objects, the content and the stories we want to tell.

For the design of the 2016 Venice Biennial Danish pavilion we presented a variety of architectural models in a multi-storey scaffold that we filled like a high-rack storage. The visitors could climb up the scaffolding using walkways and stairs. New and varied perspectives and points of view were created in this manner. The models became a series of surprising encounters as you made your way through the room.

Independent visitors

Unlike books, exhibitions are non-linear; they are spatial, one stands in the middle of them, one feels and experiences them. Much like a film our exhibitions have a dramaturgy and a screenplay but the audience can move freely within that framework and determine his or her own timings. Depending on the time they have or their interests, they can choose to immerse themselves more deeply. By breaking down the layers of information the different interpretations of the theme, and the exhibits shown, can be conveyed in such a way that the objectivity of the information is not the primary focus, but rather the context of place, time and author is. Instead of communicating messages, spaces for thinking are created. This move turns an exhibition into a public platform and the museum into a place for discourse. In the spirit of a democratic co-lab we deliberately wish to strengthen the visitor’s autonomy. As a rule we look to break with more conventional grids and structures. Visitors are generally well-informed today and do not need guidance in the classical sense. Our exhibitions take this into account by dispensing with spatial and interpretative guidelines in favour of multi-perspective and multi-dimensional approaches.

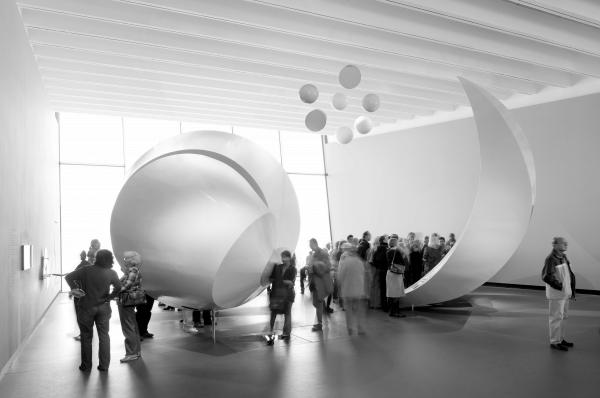

The Heimatkunde exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Berlin was characterised by a major spatial intervention. The existing room proportions were pierced by a white cube places inside the old Baroque building, which partially doubles the space. The exhibition structure was additionally slightly rotated and tilted, which initially caused irritation when visitors entered the room.

Alienation effect through abstraction

Our handling of the space continues with the manipulation of the exhibits. Original objects become decontextualised in an exhibition, when they end up in a museum they find themselves in a context they have never been in before. Things become interesting when this new environment is used deliberately. A certain alienation effect through abstraction can open up new perspectives.

In the Military History Museum Dresden Daniel Libeskind’s architecture allows objects to be presented quite differently. The children’s carousel "vehicles" installed on the tilted walls, or the helicopter plunging down a shaft-like space, take on the architecture’s expressive design vocabulary and reinforce it.

Often there is a certain reluctance to create a strong aesthetic impact when it comes to original artefacts. But why should we renounce on an emotional installation or performative presentation? We do not believe that authenticity and staging weaken each other or are mutually exclusive. Ultimately it is always about how you can ”trigger” visitors or sharpen their senses. Intriguing or irritating spatial images encourage people to discover things and grapple with a topic. It can therefore be that an unexpected medium becomes the support for exhibits. In the REN exhibition a dragon sculpture made of disposable chopsticks served as a presentation landscape for the pieces. It is clear therefore that for each exhibition we develop a higher-level design that significantly influences the visitor experience and forms a unifying spatial feature for various narratives. This setting works like a filter — both aesthetically and in terms of content — and becomes the hallmark of any exhibition.

The design of exhibitions remains one of the last disciplines where, despite growing specialisations and ever more complex technical requirements, a generalist approach is at the same time a prerequisite and the method; scenographers are also moderators, designers and the first fictional visitors. Nowhere else in interior design is the reaction to content, form and space as immediate as here. This experience should be accessible to all. That is why we call for the opening of museums in which, and on which, we work.

Published in DETAIL Inside 02/11/2017